Saving the Glen Stream

A few years ago some generous donors gave Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden seed funding to save a stream. This unassuming stream, the Glen, cuts its way across Parking Lots B and C on our campus and stretches roughly 500 feet before leaving the property. The area has been overrun by invasive plants, such as porcelain berry and English ivy, and has long been subject to pollution runoff from neighboring properties and paved surfaces in the urban environment. Due to COVID-19, we experienced substantial delays with the complicated environmental permitting process to do the work, and the huge demand for contractors, with not enough workers, has complicated matters. But the good news is that those permits are now in hand, we’ve hired a contractor, and we’ll be breaking ground in the new year on the Glen Stream environmental restoration. Thanks to the support of the Virginia Environmental Endowment, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, Dominion Energy and a private funder, we can start rehabilitating the stream so that it is healthier.

Currently, the grassy area provides the only buffer between the parking lot and the Glen Stream. The plan is to add additional grading and native plantings to slow down the flow of water and remove pollutants.

We will be restoring the stream by removing the overgrown invasive plants and replanting them with native plants. Natives provide better living space and food for pollinators, ranging from bees to birds and more. We will also be restructuring the stream itself. This will help us avoid erosion when it rains and will provide a better space in which all our aquatic life can thrive. Rebuilding the stream in this way will also help control really big flow rates when we get massive amounts of rain. Remember that record-breaking storm on September 19, 2021? A rain event like that can cause serious damage to a poor-draining waterway like the Glen Stream. By creating a better channel for the stream, we will be helping reduce its flood risk during these increasingly intense storms.

Monitoring the Environmental Restoration of the Glen Stream

With construction approaching, one of my responsibilities as a gardener at Lewis Ginter is to take some basic “before” measurements — sort of like a before photo in a remodeling project. In order to really see where we’ve made progress over the course of this project, we want an understanding of our starting point. We do this by collecting all our information before the project actually begins. We can then compare it to information we collect after the project is done to see what has changed. We are looking to take measurements of things that are impacted by the health of the Glen Stream ecosystem. We test water quality and note the presence of frogs and toads, what populations of birds are living in the area, and the presence or absence of aquatic macroinvertebrates (these little critters are any organism without a backbone that is big enough to be seen with the naked eye—insects, clams, worms). All these can tell us a lot about how healthy a stream is. For this project, we sampled two areas along the Glen Stream: one section located in the Glen and one located further downstream in the Vale, a wooded area closer to Bloemendaal House. We chose to sample in the Glen because this is where the actual restoration project will be taking place. We chose the Vale to determine what impact the restoration will have on water further downstream.

The way I go about collecting these stream insects for identification can be a little messy! First I have to get all my equipment together. When I’m sampling, I need tall rubber boots called waders, a special net with tiny holes in it called a D-net, and a bucket. Then I have to make my way down to the stream, which can get really overgrown. Once I’m finally down in the streambed, I’m ready to begin my sampling. Aquatic macroinvertebrates like to live in undisturbed areas, and they can often be found along the bottom of a stream or under rocks. This means that as I sample, I am trying to stir them up from their homes so that I can catch them. I start by shuffling my feet along the ground. If there are any big rocks, I like to use my hands to mix them around. Doing all of this will help the tiny insects float around in the water, where I can scoop them up in the D-net. Every time I scoop through the water with the net, I make sure to dump the contents into my bucket. When I have completed this process along the entire area I blocked off, I take everything back inside to start identifying, or processing, what I have found. To do this, I use a big tray and a handy identification key, created by the folks at Virginia Save Our Streams. Because I have usually collected so much material and extra debris while I sample, I have to process it in small pieces. I start by adding a little water to my bucket to help water it all down a little. I then dump about a cup of the sample onto my tray. Using my ID key, I carefully comb through the sample and count out each and every moving thing I see. Then I record the name of the organism and how many I found on my datasheet. When I’ve gone through a tray-full, I dump it into a separate bucket and start again with the next little bit of the sample. It takes a while to do, but when it’s all done, the results are very rewarding.

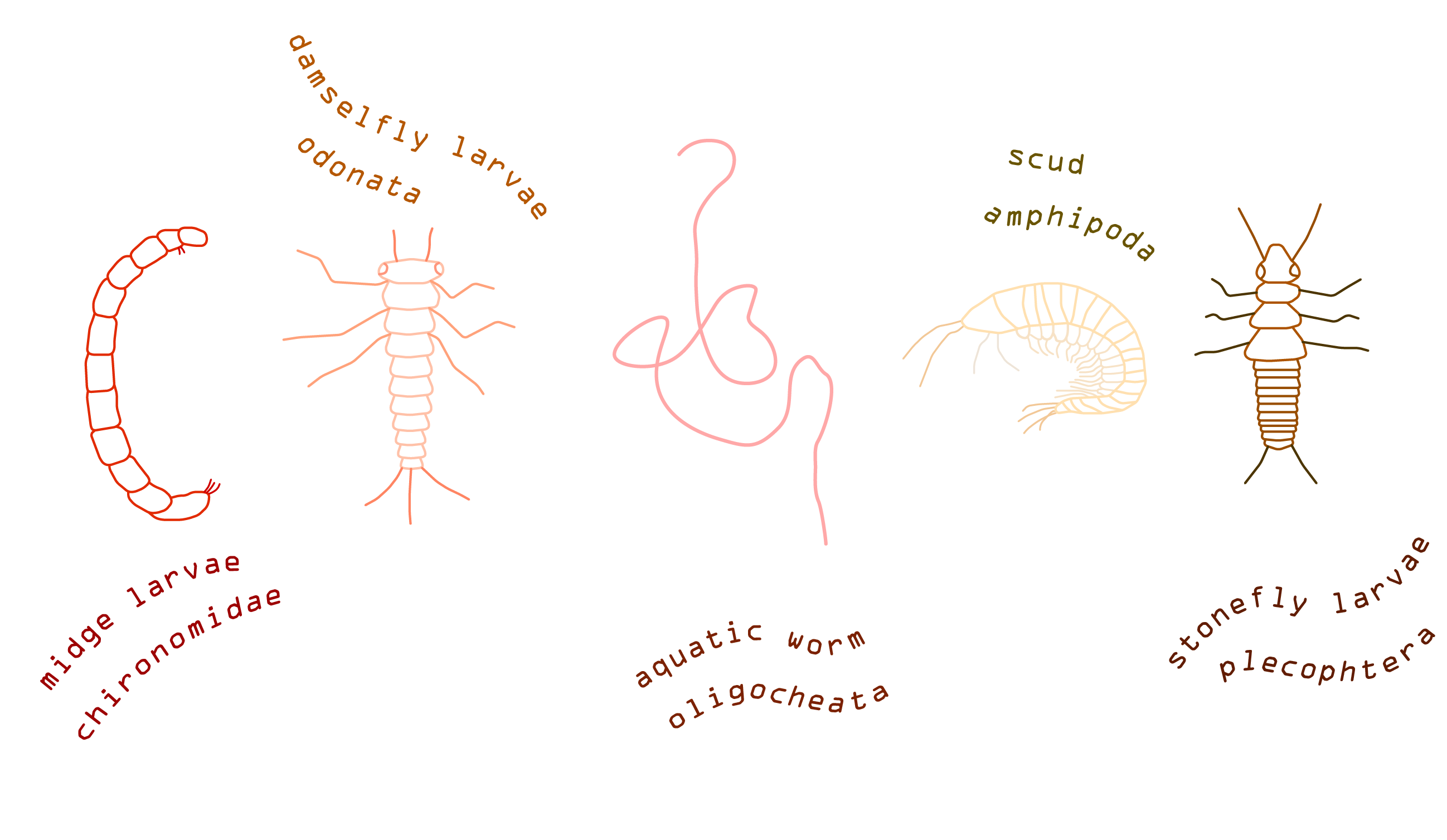

Some of the organisms that I found during my sampling included aquatic worms, scuds, midge larvae and damselfly larvae. Aquatic worms are thin, wriggly worms that live in the water and are usually no wider than a strand of hair. I always know when I’ve found a scud because it reminds me so much of a really tiny shrimp with a clear body. They like to scoot around quickly across the tray as I count samples. Midge larvae are usually bright red worm-like creatures that are no longer than an inch. They eventually turn into a type of fly called a midge fly. I also found a small number of damselfly larvae, which was quite exciting. While very similar to dragonflies, damselflies are typically a little smaller with slimmer bodies. They are one of the macroinvertebrates that can be an indicator of a healthier stream.

From left to right: midge larvae, damselfly larvae, aquatic worm, scud larvae, and stonefly larvae. Illustration by Catherine McGuigan.

After I completed my count, I had a much better understanding of where both the Vale and the Glen stand on the health scale. This measure of health can be determined in a few ways; I used the Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index in my assessment. This index helps biologists gain a better understanding of the diversity in an area. Habitats with greater levels of diversity, meaning more types of plants and animals in them, tend to be a lot healthier than those with lower levels of diversity. By counting up the number and type of each organism I found, I was able to use the Shannon-Wiener Index to determine that our streams could be healthier. While this isn’t a great result, it is what we were expecting. Subject to pollution from fertilizers, runoff, and other variables, the stream as it is isn’t quite set up for success. We hope that when we do more sampling like this over the next few years, we will see a big increase in the diversity of these aquatic macroinvertebrates.

If you’re interested in learning more about how you can help protect a stream near you, visit the Virginia Save Our Streams website. You can also become a volunteer stream monitor yourself – simply complete this online training and find monitoring opportunities near you!