Paintings from Erling Sjovold: Old River, New Shore

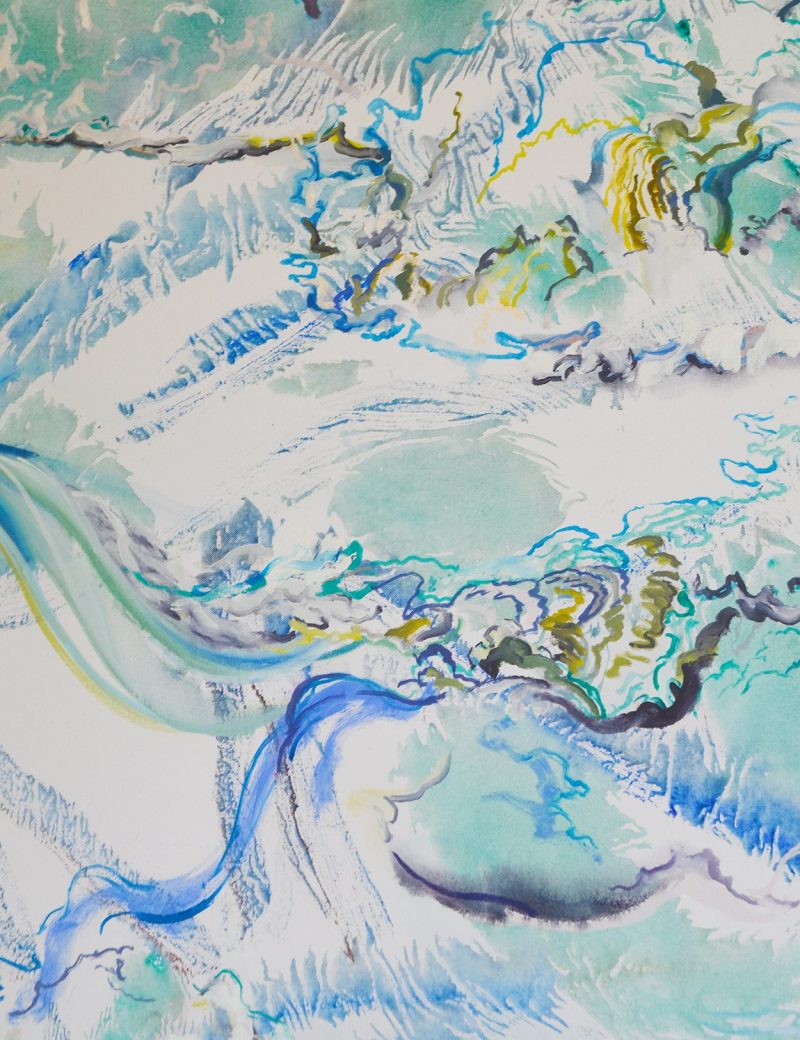

As fall begins, I am reminded of the systems in nature that transform place. The new art exhibit in Ginter Gallery II features Richmond artist Erling Sjovold’s paintings from Old River, New Shore. Old River, New Shore meditates on the transformative power of the James River and shifting environments. Sjovold’s depictions of the beloved James River reflect ideas of the uncanny, memory and the power of nature.

Artist Erling Sjovold is a professor of art at University of Richmond. Combining plein air paintings with larger-scale compositions, his paintings fluctuate between reality and the surreal that is both familiar yet displacing. I asked Sjovold few questions about his current exhibit in Ginter Gallery II:

Q: When did you start working on Old River, New Shore? What drew you to the James River as the subject?

Erling Sjovold: I started Old River, New Shore in summer 2011 while a resident at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. I’ve been painting the James River for the 17 years I’ve lived in Richmond. I’ve always enjoyed the outdoors for painting and hiking and to have this rich and dynamic river running right through the city is incredible. I’m drawn to the river’s ever-changing states, its high and low stages, roiling and mirror-like, the colors and weather accompanying those changes. The river is challenging and rewarding to paint. It’s a new river every time I visit. You never step into the same river twice, as Heraclitus said.

Q: With the combination of plein air paintings and abstract paintings in the exhibit, the viewer weaves between reality and fiction, the familiar and unfamiliar. Do you mind talking about the uncanny or surreal aspect of your work?

ES: I often sense the uncanny while repeatedly visiting and painting the same location, because it both is and isn’t the same place. The uncanny is that sense of the familiar experienced as unfamiliar, or more properly the other way around, the unfamiliar felt as strangely familiar. The river often redefines itself overnight after storms, erasing familiar landmarks and offering new ones. That push and pull of the uncanny—attraction and repulsion, placed and displaced—interests me with these river paintings.

When I tune to the more openly, or deliberately, subjective experience of the river, with multiple senses, memory’s reworking of experience, and generous interpretation, things can become strange and wonderful. Once I leave the river, I reflect upon what I felt as much as saw, what I was trying to express against what I actually achieved. Memory recalibrates my experience. It adjusts my palette to reflect a more subjective sense of light, color and place, and accommodates the psychic scale of events, rather than the observed scale of events where space and perspective assign significance according to form’s proximity or distance.

With memory I anticipate the river, only to be shocked and dispelled upon observing the river directly. And so the cycle of observation and memory goes, infinitely incomplete, energizing, satisfying, and strange. From memory, it is a short step to dreams and their believable fictions. I find also that acclimating to a solar or geologic clock, rather than that of business time, works steadily upon one’s imagination. Ironically, it is often with the more conventional, smaller plein air paintings where things get strange once you begin to think at length on the absurdity and conceits of trying to fix a moving subject in paint.

The cohabitating plein air and abstract paintings began from a “failed” plein air session one day at the river. It was flood stage, and I painted faithfully the river as I saw it, with its crazy frothing water. As I finished, I realized that the painting, however faithful to sight, had little to do with what I had truly been paying attention to: the river’s numbing white noise of crashing water. My ears were desensitized. My attention was on the physical force of the river – its speed and sound – not an appearance to be captured. I enjoy the plein air paintings greatly. The abstract paintings offer a parallel counterpart that I enjoy equally. These different ways of experiencing the river belong together. The river is never a singular thing – it is always varied and fluctuating, always being negotiated as sensed and thought.

Q: At the same time, in your paintings, the push and pull of river is mimicked by gesture and color; the fluidity is turbulent and calm, violent and serene. The color and light is energetic, yet harmonizing. It seems like the flux and power of the river and landscape is important to this work. Can you talk about these contrasts? How do they connect to your idea of the sublime?

ES: I first encountered the river in late summer, early fall, when its water was relatively low. The river seemed accessible, shallow, mostly gentle, plenty of outcroppings, people swimming. I’m not naïve about the deceptive nature of rivers — the serious play between surface and depth, the hidden hydraulics — but once I saw the effects of big rains raising the James, I was spellbound. What an abrupt transformation and unimaginable power! I often visit the Pony Pasture when it floods, to paint, photograph and just watch. Seeing the enormous, uprooted trees that the river carries like matchsticks towards the sea, considering the force of those logs as a physicist might, is awesome in the true sense of the word. And it is sublime, both entrancing and threatening.

The sublime is an elusive quality or state of being to define. It becomes even more confusing, compelling and elusive to me in our era of extreme weather, or climate change, where we contribute to an unprecedented, unpredictable climate that envelopes all of our being. If the term sublime has suffered from overuse in its reference to landscape, it has been meaningfully revitalized for us now. Climate is sublime.

More humorously, I’m reminded of the river’s force every time I see a group of four or five strong, restless, visitors attempt to rock and dislodge one of those large logs from its resting place on a rock or driftpile. Activities worthy of a YouTube post.

Q: With the movement of the river, there is creation and destruction. In your paintings, there are structures that are created by tree limbs – archways, pyramids, windows, portals – the river takes down material with its awesome force, and builds it onto the rocks; the river shapes and weathers the rocks over time, and when that sediment settles, new rocks form. There is this constant renewal and destruction and the river is the architect. Can you tell me about these structures and the role(s) the river plays to you? What about the role of color in your work?

ES: I like your thoughts on the structures of the tree debris. These structures are often discovered as much as sought. Through the act of painting they begin to resonate as forms and spaces, relationships of color, movement and texture. I tend to heighten the dynamism of these structures by orienting my compositions vertically, ascending and descending, diagonally bracing movements, remotely similar to Chinese landscapes, and against Western-European landscape’s conventional horizontal rest. Some of the structures become literal as a habitat, refuge, perch, den, or scaffold based on observing animal adoptions of these structures. Sometimes these found structures suggest content from other contexts like architecture, dance, psychology, memory, history, time, etc.

For example, there is a stretch of small river islands between Huguenot Flatwater and Pony Pasture where the upriver heads of these islands accumulate the driftwood, while their downriver tails remain free and unencumbered. A critical mass gathers at the head until a big storm clears it away, or delivers a completely new mass to the head. This process dramatically alters the form and silhouette of the island. I liken it to a portrait subject emphasizing its inherent asymmetries. I also think of these islands as “catch and release” metaphors for historical memory and psychic debris. The river constantly is cleansing the detritus it delivers.

Color may be the most obvious aspect of my painting. It may also be the most private. It is my intuitive driver, trusted as purposeful even if I cannot always locate or name its purpose. It is simultaneously immediate and elusive. Color is light and light is color. I use color to describe the illusion of sunlight on water and trees, to express an abstract idea, to simply engage color’s material presence. Color also complements the analytical, critical awareness I bring to painting. Color’s dependence on context makes it difficult to fix; its unstable, relational status can defy rational ordering of space. Color concerns my pleasure and indexes feeling most immediately. Color affirms and risks, such that its negation speaks as powerfully as its primary state. I find it complex, resonant, renewing and fundamentally present.

When painting, I greet the river mindful of what I’m bringing to it in terms of attitude and thoughts while looking for its changes and similarities. While I discover interesting metaphors, I don’t personify the river often, but if pressed, it’s like engaging a brilliant, generous, challenging, and ultimately, aloof collaborator in whose silence it’s implied that I must look closely, think deeply, empathize fully, listen intently, imagine wildly and paint freely if I am to “get it”.

Old River, New Shore is on display now through November 6.

Old River, New Shore: Paintings by Erling Sjovold

Ginter Gallery II, Kelly Education Center

Free with garden admission.