By Hook or by Crook: The Plunder of Orchids from the New World

by Victoria Waiton, Membership Assistant, Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden

On my most recent trip to the Conservatory, I tried to remember what it was like to see a cascade of Oncidium orchids for the first time, and wondered what it would feel like to walk through a forest and suddenly come across the dramatic sprays of delicate yellow blooms in the wild. When Europeans saw orchids for the first time, it set the botanical world on fire, igniting an obsession that continues today. Now, we can buy inexpensive orchids in almost any nursery, home improvement center, or grocery store, but 19th century orchids were an extravagance reserved for the nobility. The danger and expense of finding and shipping the blooms from far-flung corners of the world added to their mystique. In 1818, when a plant shipped to England by explorer William John Swainson flowered into Cattleya labiata, demand for the showy, exotic plant gave birth to the professional orchid hunter who made his living finding new orchids to feed the European market. The most famous of these was Czech gardener Benedict Roezl.

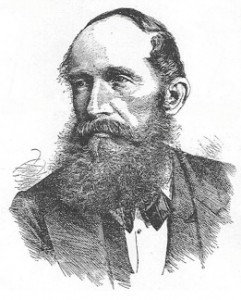

As a plant hunter, Bendict Roezl was inefficient, even wasteful. He was harried, easily distracted, careless, and illogical. Still, he was the best: if Frederick Sander’s nurseries made him the King of Orchids, Roezl, who did the dirty work of travelling the world to collect Sander’s orchids, was the Prince. The most accomplished plant hunter who ever lived, Roezl was a trailblazer whose passion drew Sander into the orchid business in the first place, a bulldozer of a man who travelled and collected specimen alone, unarmed, and mostly on foot. When he met Sander, Roezl was already a famous traveller, but that’s not how he started out. His former life as a planter had ended abruptly when he tried to mechanize the process of extracting fiber from his textile plant, Boehmeria tenacissima. The machine Roezl invented, pushed beyond its limits at an exhibition, crushed one of his arms in its gears. The limb was replaced with a prosthetic, an iron hook, which made farming impossible but gave the six-foot-two blond a look of rugged distinction. So Roezl started over as a plant collector, and the hook impressed the people he encountered in his travels throughout the Americas.

Discovering 800 species of flowering plants and trees that had never been seen outside the New World, including many orchids that he sent home to Sander and other patrons, Roezl was celebrated but never amassed much wealth. He never published, either; his life can only be pieced together from his letters and a handful of campfire stories. In these stories, Roezl emerges as a man distracted by his passion for the hunt.

In the nineteenth century, an orchid hunter’s job was to scour the world’s jungles, forests, and mountaintops to collect and ship new species to Europe to be sold for profit. A plant hunter, or traveller, stripped areas bare of entire populations of orchids to prevent them from falling into a competitor’s hands. In some ways, the orchids exacted revenge: a traveller rarely made enough money to live comfortably and often met with a grisly death by wild animal, a slip off a rocky cliff, or murder by locals. More than half of the harvested orchids perished from disease, pests, and exposure to seawater before reaching the nursery or botanical garden that sponsored their voyage, and as many as 20,000 plants could be lost at once in a shipwreck. Sander was forever worrying over the status of the orchid shipments en route to his nurseries as Roezel raced around North, South, and Central America at high speed, never staying in one place long. Dr. Heinrich Gustav Reichenbach, the German orchidologist responsible for identifying and classifying many of the orchids arriving in Europe, criticized Roezl for his carelessness in packing plant specimens, which made it difficult to draw accurate diagrams of new species. Sander also expressed displeasure in Roezl’s sloppiness. The director of the Zurich Botanical Garden, which received many of Roezl’s plants, condemned his wasteful collection practices, believing them to be outdated and environmentally irresponsible. Roezl seemed singularly interested in the discovery of exotic new plants and not at all concerned about their preservation, a sentiment his fellow orchid hunters probably shared. The work was dangerous, but Roezl carried no firearms and was constantly robbed and prone to serious lapses in judgment. Passing through Denver, the story goes, Roezl gave his life savings to an innkeeper for safekeeping and was surprised when he returned from a mountain expedition to find neither hide nor hair of the innkeeper or the money. In another vignette, a jaguar wandered into his tent and Roezl was convinced that the cat did not eat him because he did not have a gun to shoot at it. Furthermore, his stubborn refusal to travel with other plant hunters left him totally dependent on the kindness of local people for food, guidance and protection.

Sander made a fortune funding these orchid-hunting expeditions. Though the risks were great, the returns on investment could be jaw dropping. Orchids sold like jewels. At the height of the mania, Sander made £2000 with the sale of one Cattleya warscewiczii f. sanderiana specimen. Millions of orchids passed through Sander’s hands. His nurseries in St. Alban (purchased in 1876), Bruges (founded in 1894), and New Jersey (set up and sold within a few years in the mid-1890s) dwarfed every other orchid operation in the world. As Royal Orchid Grower to Queen Victoria, Sander dazzled her majesty with opulent bouquets of orchids from every corner of the British Empire.

He honored the Queen by dedicating to her volume one of his Reichenbachia, a collection of exquisite life-sized orchid illustrations, chromolithographs of which are on display in the Garden’s Ginter Gallery II graciously on loan from Dr. Arthur Burke, an expert grower of rare and unusual orchids, and friend of the Garden. (Selections from the Reichenbachia runs through April 22.) Turn-of-the-century auction houses offered wild orchids in lots of hundreds or thousands to the well-heeled elite. More importantly, however, Sander’s grand-scale domestic orchid propagating gradually made orchids affordable to the middle class.

Roezl died in 1884 at home in bed, with no jaguar in sight. Sander partnered with new plant hunters. Orchid mania waned as the domesticated version became more accessible and wild orchid hunting became increasingly unnecessary. Sander lived until 1920 and his nurseries at St. Alban and Bruges remained profitable until after World War II, at which point they closed their doors. Orchids haven’t lost their allure — Americans now spend more on orchids each year than on any other houseplant. Orchids Galore! provides the opportunity to experience hundreds of orchids from around the globe and learn how they made the journey from jungles, forests, and mountaintops to American homes. (Don’t delay–the exhibit is only here through April 22!)

Though 19th century plant hunters like Roezl wreaked havoc on wild orchid populations by taking as many plants as they could get their hands on, nurserymen and botanists on the receiving end in Europe made the most of the orchids that survived the journey. Through propagation on a massive scale, Sander was able to make orchids inexpensive and widely available without further endangering wild populations. Victorian plant hunters sacked Earth’s jungles in blissful ignorance, but in this more enlightened age, strict conservation laws protect orchids in the wild. Mercifully, the days of savagely pillaging entire populations of orchids for the mass market are long gone. Few known species are endangered today — none on display at the Garden are threatened with extinction, though many are rare.  The Garden shares the vision of Orchid conservation organizations worldwide with the shared goal of protecting endangered orchids and conserving their unique natural habitats. Ninety percent of all orchids are now grown in nurseries, says Kew Gardens, whose experts also suggest we have probably seen the end of new orchid discoveries. The golden age of orchid discovery, led by romantic explorers, is past. The age of conservation is still in its infancy, however, and that’s a movement that’s up to all of us to lead.

The Garden shares the vision of Orchid conservation organizations worldwide with the shared goal of protecting endangered orchids and conserving their unique natural habitats. Ninety percent of all orchids are now grown in nurseries, says Kew Gardens, whose experts also suggest we have probably seen the end of new orchid discoveries. The golden age of orchid discovery, led by romantic explorers, is past. The age of conservation is still in its infancy, however, and that’s a movement that’s up to all of us to lead.

For Further Reading, Visit Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden’s Lora Robins Library:

Coats, Alice M., The plant hunters: Being a history of the horticultural pioneers, their quests, and their discoveries from the Renaissance to the twentieth century. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1970, c1969.

Lyte, Charles, The Plant Hunters. London: Orbis, 1983.

Tyler-Whittle, and Michael Sidney, The plant hunters: being an examination of collecting, with an account of the careers & the methods of a number of those who have searched the world for wild plants. New York: The Lyons Press, 1997.

Swinson, Arthur. Frederick Sander, The Orchid King: The Record of a Passion. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1970.